picture by José Manuel Soares

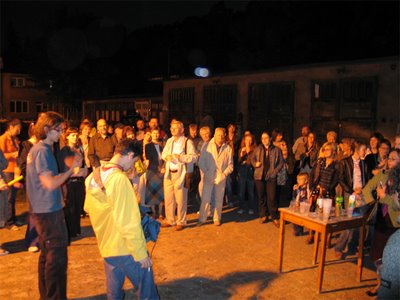

But he doesn't wait till the day of presentation. Instead, he organizes a vernissage a few days earlier. He invites the broadest range of people possible: art curators, family, security guards, businessmen, construction workers from a site nearby, distant relatives...

But he doesn't wait till the day of presentation. Instead, he organizes a vernissage a few days earlier. He invites the broadest range of people possible: art curators, family, security guards, businessmen, construction workers from a site nearby, distant relatives...

There is, of course, an opening ceremony...

There is, of course, an opening ceremony... ...during which the artist speaks about everything one expects him to - and more...

...during which the artist speaks about everything one expects him to - and more...

Some of the questions are: Can you descroibe the best work here to someone who isn't seeing it? Why is it so dark in here? What texture do you like objects to have? Why? Do you ever feel like touching objects? Do you think it depends on you or on the objects? Doesn't this pink wall irritate you? Why dogs? Is there any work you don't like particularly? Can you describe it to someone who isn't here?

Some of the questions are: Can you descroibe the best work here to someone who isn't seeing it? Why is it so dark in here? What texture do you like objects to have? Why? Do you ever feel like touching objects? Do you think it depends on you or on the objects? Doesn't this pink wall irritate you? Why dogs? Is there any work you don't like particularly? Can you describe it to someone who isn't here? Like children. This is what I like about it. What could have become a somewhat annoying conceptual work about absence became a reminder of the experience of art. Of our contact with it, and how much an unfinished dog with square legs can mean to us. Even once its gone.

Like children. This is what I like about it. What could have become a somewhat annoying conceptual work about absence became a reminder of the experience of art. Of our contact with it, and how much an unfinished dog with square legs can mean to us. Even once its gone.

CNN reports:

Mo Xiaoxin, a 56-year-old assistant professor at a university in Changzhou, in eastern Jiangsu province, shocked students by stripping during a lecture on "body art" to emphasize the "power" of the body and to "challenge taboos," the Beijing News said.

"There are no taboos in the field of research, but to do this directly in the course of teaching is obviously not appropriate," the paper quoted Tian Junting, a culture ministry official, as saying.

The lecture was part of a course within a newly established "human body art and culture" research institute -- China's first -- at Jiangsu Teachers University of Technology, the paper said.

Mo arranged for four other models, including a man and woman in their 70s or 80s, and a younger couple, to strip naked in front of the class while he lectured, the paper said.

If we accept that a significant part of contemporary art looks to go "out of the box", teaching it becomes a challenge. Trust me, I know. The whole idea is how to get someone to accept the excentric as central, i.e., how to see ("alternative") contemporary art as a basis, or a context for work. This is extremely difficult, much more difficult than just learning to appreciate it. On one hand, the students need to comprehend the strength of new works, the impact they potentially have; on the other, it's not enough to see it in a distance, in an attitude of all-encompassing tolerance. This - body art, performance, controversial or plain shocking installations - is to be, if not a foundation, at least a contemporary history. That means, it needs to be close enough to be useful, to be felt as something we might have done, but (often fortunately) don't need to do any more.

Does this mean the teacher was right? Only if he achieved his goal. Only if the people watching him not only got the point (their point, not necessarily his point), but also, will feel empowered through the experience.

But teaching it? Or: actually doing body art (if getting naked comes anywhere near as much as an introduction to body art) in front of the students? Two points irritate me here:

1) A teacher that instead of making the students discover things by doing them does them himself is at least suspicious. I'd rather have a scandal where the teacher convinced students to actually do body art. At least then, they are the performers, and not just forced spectators. The article states that the teacher tried making the students undress too. It seems it didn't work. Was there any room left on the stage?

2) On a more personal level, art that aims to "break taboos" rarely ever speaks to me. It's not too hard to watch. It's too easy. As one ex-body artist said, the performers are not the only ones sweating. The audience sweats too - of a specific embarrassment and more often than not, a deep desire to be somewhere else.

My doubts regarding Mo Xiaoxin are both as a teacher and a perfomer. But they have little to do with indecence.

Flowing in the baroque wilderness of fleshy forms, diving into the realm of whatifs and whynots, is a delicious project called pixelnouveau. Explore it, get lost in it as I did, discover the scent of digital daydreaming...

Flowing in the baroque wilderness of fleshy forms, diving into the realm of whatifs and whynots, is a delicious project called pixelnouveau. Explore it, get lost in it as I did, discover the scent of digital daydreaming...

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje Van Bruggen, Cupid's Span

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje Van Bruggen, Cupid's Span Jeff Koons

Jeff Koons

I am for an art that (...) does something other than sit on its ass in a museum.So, in the case of Oldenburg, where is all this art gone? What is it that makes one move from the majestic art of dog-turds to huge post-ready-mades? Could size-ism be a form of escapism?

I am for an art that grows up not knowing it is art at all, an art given the chance of having a staring point of zero.

I am for an art that embroils itself with the everyday crap & still comes out on top.

I am for an art that imitates the human, that is comic, if necessary, or violent, or whatever is necessary.

I am for an art that takes its form from the lines of life itself, that twists and extends and accumulates and spits and drips, and is heavy and coarse and blunt and sweet and stupid as life itself.

(...) I am for the art that a kid licks, after peeling away the wrapper.

I am for an art that joggles like everyones knees, when the bus traverses an excavation.

I am for art that is smoked, like a cigarette, smells, like a pair of shoes.

I am for art that flaps like a flag or helps blow noses, like a handkerchief.

I am for art that is put on and taken off, like pants, which develops holes, like socks, which is eaten, like a piece of pie, or abandoned with great contempt, like a piece of shit.

I am for art covered with bandages, I am for art that limps and rolls and runs and jumps. (...)

I am for the art of underwear and the art of taxicabs. I am for the art of ice-cream cones dropped on concrete. I am for the majestic art of dog-turds, rising like cathedrals.

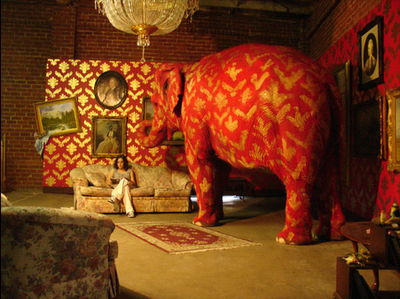

The power of his work lies in the way it interacts with its environment and that obviously gets lost when you put it in any kind of gallery setting.I guess my wish came true.